Basic Systems

By Matt Richter

In my last post, I introduced the concept of systems thinking and simple systems. Now, I would like to dissect that a bit more and explore how one can conceive of a system and the basic relationships within that system.

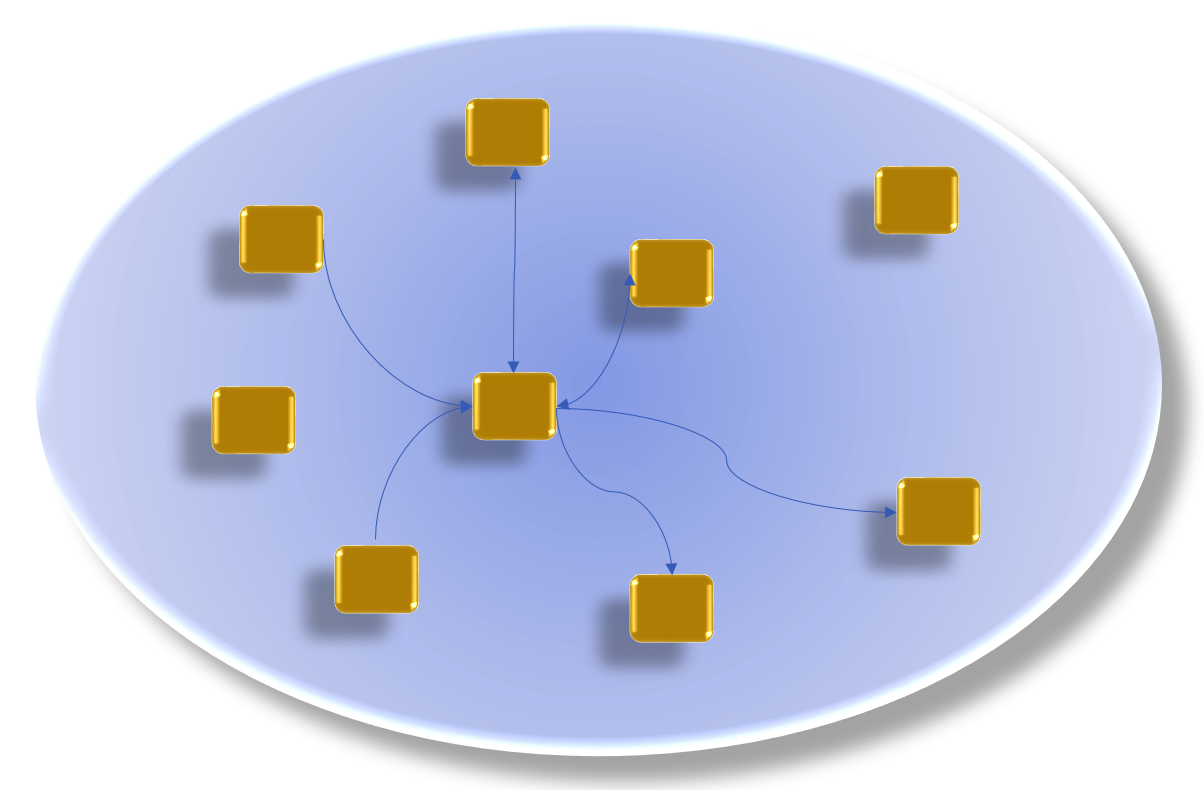

To begin thinking about a system, you have to see the system… on paper, or at least in your head. Start by thinking of a system as a circle– or in this case, more precisely, an oval. The items inside a system are the elements. They can be people, other events, activities, resources, etc. One element will affect or influence another or several elements. And of course, other elements can influence or affect that one. You can also have elements affect each other.

The way an element influences or affects another element is through processes. The input is the influencing element. For example, French regulations on how degree issuing schools can hand out degrees is an input for me on how I design courses within the EMBA program at emlyon. That body of rules informs how I work with the students in those courses. The process is how the inputs engage with me. For me, the emlyon instructional procedures dictate HOW I build my course according to the rules-– and, -- and here is an incredibly important part of systems thinking– other inputs. Other inputs might include, in this example, instructional design principles, my own experiences, colleagues with whom I collaborate with on this course, and others.

You can also think of these interactions as WHATs– the elements in the systems and HOWs the methods by which they interact with each other.

Now, if we go back to our simple map… in reality, very often there is more interactivity, more interconnections than we anticipate, or assume. Sometimes, we assume that influence is just one-way. But that could be due to our limited experiences, our limited assumptions, our biases, all which render it extremely difficult to see, or be aware, of all the factors that influence or are affected by events within our systems.

Now, take the main focus of this simple system highlighted by the small circle. Note that only five of the elements directly input it. Those further away may only influence indirectly by influencing those more directly that influence our guy directly.

You can start to see how this gets complex… quickly.

A great example of influencers in a system affecting the central part of that system is the great toilet paper debacle during COVID.

While many assumed that the great 2020 toilet paper shortage in the US (resource: https://cnr.ncsu.edu/news/2020/05/coronavirus-toilet-paper-shortage/) was a result of supply-chain issues, this actually wasn’t the case. In fact, 99% of all toilet paper in the US is manufactured in the US. No supply chain issues. The debacle actually has to do with inputs and outputs further out in the process influencing influencers. In 2020, grocers, who are the largest retailers of toilet paper are direct influencers in the system. Their process was to keep only a few weeks’ worth of paper in their stockrooms. But the end users (further out in the system changed their buying habits as a result of fear and the assumption toilet paper would be unavailable (a self-fulfilling prophecy, mind you). And since folks were staying home, the user demand for commercially bought toilet paper plummeted. Commercial toilet paper (TP for offices and other public places) is made typically in different factories. And of course with people staying home due to the COVID protocols, they were using more toilet paper at home than they typically would have done so.

In other words, an event (COVID) led people in the system (USERS) to change how they engaged in the system (BUYING TOILET PAPER) causing others in the system (RESELLERS) to have to notice the change in behavior of their buyers, leading them to put on new requirements of their suppliers– who were not set up to quickly adapt, and so forth.

But, this is my analysis (and that of several journalists) of what is called the system dynamics– the adaptive and organic shifts that often occur in a system– the changes that happen.

My analysis is one type of systems thinking.

As you can see, the narrative for what is going on is not just complex but perilously dependent on how accurate my data, my information, is about this system and the toilet paper shortage. And, an overly simplistic analysis can lead to very bad decisions. For example, if I went with the faulty assumption the shortage was supply chain related, I might make a host of decisions that would lead to more problems.

Or, I might over complicate my analysis and over react in a different way.

THE KEY TO SYSTEMS THINKING IS TO DETERMINE HOW THE ELEMENTS IN A SYSTEM AFFECT EACH OTHER.

So, as we consider the interconnections of our events, we need to factor in three areas:

How the people in the system engage with each other. Those aforementioned RELATIONSHIPS among the various elements in the system. Why? Because humans have a tendency to screw up everything!

THE HISTORICAL. We need to understand what happened in the past that got us here today.

And think tomorrow… but take a slightly negative view… think about what could go wrong. What are the risks we need to consider that can affect our system? RISK MANAGEMENT— or, future, potential problems.

But wait! There’s more to it!

Systems thinking– especially as we delve into the interconnectivity amongst the various elements requires us to become aware of many aspects of the relationships we may or may not think about in our own, personal considerations. In other words, the HUMAN FACTORS.

MOTIVATION

POLITICS

TRUST AMONGST PLAYERS IN THE SYSTEM

We need to consider the motivation of the different players. We need to understand why those involved do what they do. For example, a simple difference between their goals and yours can completely derail a system.

Politics is defined as the interplay between two or more people engaged with each other. Politics is by itself neither good or bad, but can be applied ethically, amorally, procedurally well or poorly. Navigating the politics within your system is essential because if you just rely on the logic of the procedures used within the system, you may miss why there is a failure. In other words, politics is the human component of the formula that makes up a system.

Ok… I know… trust is inherently a component within the realm of politics. But it is a BIG ONE! So, let’s call it out separately for kicks and giggles. Trust– A lot of behavior is often driven by trust or a lack of trust. But, as a systems thinker, do you know the various factors that embody trust?

A failure to understand the interplay these human factors play can fully derail your system.

I’m a big fan of James Burke’s CONNECTIONS programs. I highly recommend them when you have some time. Burke is a science journalist who explores the interconnections of something very disparate from something else. He then shows how the two are utterly connected by one event in the past leading to several in the future that lead to more events and still more. That you don’t get where we are today– your system, without building on what came in the past. Burke states that people only know what they know at the time. They have no idea ultimately where their actions will lead. Predictions and forecasts are merely conjecture. And rarely are we aware of how we got where we are.

Why does this matter? Because it is the argument for us to engage to two activities.

The first is ROOT CAUSE ANALYSIS– something we will dive into deeply in a future post. Root cause analysis is the study of exactly what Burke claims most of us don’t understand. How we got where we are. It is the study of why something actually is happening and the factors that support (or undermine) it continue. Good systems thinkers become good root cause analyzers.

What this means is that a big part of systems thinking is problems solving, and more importantly, critical thinking.

And the other tool we will use as we explore how the various elements in our system interconnect is RISK MANAGEMENT. A risk is a potential problem. It hasn’t happened yet. Our job is to forecast the likelihood a potential problem will happen and if it does, the impact that problem will have on our system.

Risks are people oriented… so those motivational, political, and trust-based factors.

They are operational… risks associated with the processes, resources, and other systems that affect ours going awry.

And financial risks. For our purposes here, these risks tend to be either input or output oriented.

When forecasting risks, we need to see as many as possible. If we don’t, we won’t be hit by the ones we do see, we will be hit by the ones we miss. So, the more we can see, the better! Once we identify those risks, we rank them according to high impact and high likelihood. The dangerous ones require a mitigation plan (how we will avoid it) and contingencies plans (what we will do if the risk turns into a problem).

One final thought on systems and their various components. I have only been talking about single systems. The toilet in my previous post. The graphics I shared in this article represent just one system. While the toilet paper shortage example is not a simple system, it is drawn as such to actually begin introducing the notion that there is such a thing as complex systems.

Complex systems are big “things” made up of multiple systems. French society is a complex system. The university of Rochester (my alma mater) is a complex system. The EMBA program where I teach is a complex system. Your work environments are complex systems. The way you may input your time at work is likely a simple system that is a part of the bigger payroll system that is a part of the bigger HR system that is a part of that company system. In my next, and final systems thinking post, we will get into complex systems. But it is essential for you to first understand how a simple system works.

So… more to come!