How Learners Are Motivated: Exploring How Rewards and Other Motivational Strategies Affect Learning Outcomes

By Matthew S. Richter

BACKGROUND

I am a trainer. I have been a trainer for just about all of my career. I started in the mid 90s and was inundated with all sorts of training games that used rubber balls, funny sounds emanating from trainers to participants, and EST-like connections to humanistic approaches in business. Frankly, this stuff drove me crazy and I was somewhat embarrassed to admit that I was indeed a trainer.

It was at this time that I met a guy named Thiagi. Thiagi was renowned as the game guy. All of my colleagues used his games and half the games I infused into my delivery came from him and I didn’t even know it. I should say, however, that my friends and I were all misapplying his activities. And we all had the misconception that training games should be fun before anything else. When I met him, Thiagi explained that fun was not what he and his activities were about. In fact, his goal was to facilitate engagement toward a performance objective. Now today, this all makes sense—but remember 25 years ago, it was all about those funny sounds and hopping around like a chicken. Thiagi talked about relevance to performance, and how every activity needed to be congruent with every performance goal. And every performance goal should have a link back to a business objective. Essentially, Thiagi was talking about getting participants to truly connect to the value of what they were learning. And he used activities to facilitate higher levels of competence. He used interactivity as a way of offering opportunities for participants to freely engage and find their own value. Thiagi was teaching trainers to create motivating environments that had significance. I was hooked.

Eventually I transitioned from a naive practitioner to someone who could do the moves properly. I had technique but no reason why Thiagi’s way of doing things worked. I probably should have just asked him. Then, I was introduced to a model that explained why we do what we do. A mentor of mine handed me a book called just that, WHY WE DO WHAT WE DO, by Edward L. Deci. It explained how and why people were motivated, intrinsically and extrinsically, to perform. The more immersed I became applying Deci’s model to what Thiagi had taught me, the more convinced I became that life truly had meaning.

INTRODUCTION TO MOTIVATION

Motivation is the energy that accelerates behavior. Often trainers and instructional designers devote a lot of effort in designing reward strategies, convinced that finding the right reward for the right participant will endow the participant with the motivation to learn. Many of us think of motivation as a “carrot and stick” kind of endeavor, with the mechanism influencing motivation originating from outside of the person motivated. This article will help trainers to choose whether to use reward strategies, and if so, how to use them wisely, with a greater understanding of the consequences of their choices.

The goal of most trainers is to get participants to engage in their program as productively as possible with the hope the desired learning objectives will be met. Many prescriptive models of motivation have been applied to help educators achieve this objective, but we will only focus on one. Self-determination theory (from the work of Edward L. Deci and Richard M. Ryan, both of the University of Rochester), is an especially useful model.[1] When applied appropriately, this model can help trainers and designers achieve effective results. Throughout the ensuing discussion on the application of rewards versus creating a more intrinsically motivated learning environment, I’ll focus on the vital role of relevance; where the more effective goal is to move participants along a continuum from being amotivated, or apathetic toward a learning objective, to becoming passionate learners for it.

These are the major objectives of this article:

Discuss the role of motivation in the training context

Explore how to leverage the use of rewards and reinforcement systems if and when they are advantageous

Explore alternatives to reward/reinforcement strategies

Encourage careful analysis of the intention with which you approach training.

Components of motivation include a sense of relatedness, a sense of competence, and a sense of autonomy. Deci and Ryan describe these components as basic psychological needs. When those basic needs get met with regard to a task, we are more likely to be intrinsically motivated to engage with that activity. These factors influence how a person’s motivation is realized, or in other words, what mechanisms drive a person to feel completely apathetic toward learning, capable, but forced to learn, or passionate to learn.

Here’s the crucial point for trainers to remember: the participant’s perception of whether her need is met is what counts. For example, a participant may come to you with a diagram that is totally incomprehensible. Your first reaction is to tell the student how great it is. Assuming the participant believes you, she walks away happy, believing she has done a good job. You and I both know the diagram is objectively poor. That is real competence (or lack thereof). The participant has perceived competence. Motivationally, that perceived competence is what matters.

Competence: Competence is the need to perceive oneself as successful at achieving a task or an activity. To feel competent, a person must believe he has the knowledge and skill to perform the task, as well as the environmental support and structure to do it. A sense of competence must be present for a person to be intrinsically or extrinsically motivated. It’s the permission-to-play factor. Without a sense of competence, one will not feel motivated at all toward the task at hand. Competence is both the capability (knowledge and skills) to do something, and the capacity (time and resources) to do it. So in a classroom setting, this means participants believe they have the knowledge and skill to learn your topic and the necessary tools and appropriate activities to practice.

Autonomy/Control: Autonomy is the perception that one has a choice (volition) in performing a task and is not influenced by any other source to do it. A sense of autonomy must be present for intrinsic motivation to occur. Control is the opposite of autonomy. Control occurs when the participant feels he doesn’t have a choice in his learning or is influenced by some external source. Clearly, if he feels forced to do an activity or memorize some silly facts, he is less likely to feel either pleasure or passion in engaging the process. Why? Because doing something perceived as meaningless undermines one’s sense of autonomy—especially if compelled to do the stupid activity. So even if he feels competent to learn, if he feels controlled, he will be only extrinsically motivated to perform. A form of reinforcement is then necessary. Often one feels volition to participate in an activity when that activity feels meaningful or has purpose. In other words, when learners perceive the inherent value of a task, they more readily engage in it. Meaning and purpose are really the underpinning causes behind one’s sense of autonomy.

Relatedness: Relatedness is the feeling that one is emotionally tied to significant others in one’s life. The relatedness need is met when participants feel “we’re in this together.” The more we can make the learning involving and participative, the better.

The more we get participants to develop a sense of collegiality, the more they are likely to play and participate willingly.

REWARDING DESIRED BEHAVIOR

In my role as a consultant, I’m called into an organization to deliver training programs that I have designed. I often don’t have a long-term relationship with the participants. I’ll be with them for perhaps a day or two. I’ve found it useful in these situations to hand out dollar bills—lots of them. I tell participants that I’m going to pay them for saying anything I deem profound or useful or smart-alecky or that might be considered heckling. Clearly, I’m rewarding them for participation. I’m offering an immediate reward, a reinforcing consequence to get them to perform a desired behavior. This is a quite useful technique when given the fact that the majority of participants are assigned the course and have no desire to be there. It helps bridge their initial apathy with potential intrigue.

I find handing out dollar bills to be very effective. Participants compete to answer questions, leap to their feet to volunteer, and keenly listen for any opportunity to show what they’re learning. Knowing I’m out of there after a day or two enables me to punish them, publicly humiliate them, pay them off, or reward them in any way that I want. I get a real short-term bang for my buck. Literally. In a recent Change Management course I taught, I handed out $250 in one dollar bills and rewarded one team a $300 cash prize for winning a game. Great for me. Great for the participants. Right?

Or, are you appalled, thinking, “I train these people again and again over the course of a year. How can I afford that kind of reward system?” Well, the downside is actually worse than that. Hang on.

The day after our Change Management workshop, a friend and fellow trainer was scheduled to lead the same 25 participants in a workshop on hard-core performance management—a fill-out-the-form type of performance appraisal training (the dead, dull boring stuff). My friend’s real problem, however, was that she had the misfortune of following me the day after I was handing out cash. After a day of money rewards, the participants were fully expecting a great payout from her, especially when I had teed her up as an exciting, awesome trainer and friend. Imagine the reaction, then, when she informed them she had no money with her to reward them. Given how completely motivated they were to earn the money, the participants joked around a lot at first. Unintentionally, I’d set her up to fail. Without the compensation, without the external rewards for participating, the participants had no motivation to engage in her learning processes.

In relying solely on rewards, then, I set up two problems: 1) I established unrealistic expectations in our participants for external rewards from future trainings, and 2) I oriented them to value the reward and not the learning (or its application on the job). Without a reward, no performance. Oops. In other words, I undermined any inherent value they may have seen or experienced with regard to the topic at hand. I associated for them a prize—one unrelated to change management (the topic)—leading them to focus on the reward instead of the benefits of getting better at managing change situations.

CONSEQUENCES OF REWARDS

In deciding to use one motivation strategy with (or over) another, we need to know the consequences of that strategy. It’s easy enough to pump participants up in the moment with a reward, whether it’s a dollar, an A, a gold star, or an award. What’s the consequence? We’re not arguing that rewards are ineffective. In fact, they are extremely effective at affective behavior change (as is punishment). Remember how well our dollar bills worked? The consequences, however, concern the consistency of the desired behavior and the quality of the behavior when it’s demonstrated. When the reward is withdrawn, so too, and often, is the behavior. If consistent behavior is required in this scenario, the reward must be consistent, too. This means you have to be ready, willing, and able to cough up the dough every single time. And in some cases, continually increase it. As an outside consultant, that is more likely to be possible than if I am an inside guy.

So we may see consistent behaviors if we keep the dollars coming, but what of the quality of the behavior? Edward Deci, in his book Why We Do What We Do, tells the story of Lisa, a six-year-old girl, whose violin teacher awarded her a gold star for every practice session she completed. When Lisa had collected enough gold stars, the teacher gave her a “treasure.” Lisa’s parents discovered, much to their dismay, that while Lisa completed every minute of her practice sessions, she did no more than was required to receive the star, watching the clock the whole time. Worse yet, her effort and diligence in learning new songs and correct fingering were all but non-existent.

Remember, she wasn’t rewarded forqualitypracticing, just forconsistentpracticing. Clearly, the consequences of the reward system inadvertently sabotaged the goal of learning. Instead of being motivated by the pleasure of playing music (and playing well), she was fixated on the gold stars. In fact, she became quite stressed out at the possibility of not meeting the expectation. Stress became the overriding emotion rather than pleasure. So, focusing on extrinsic factors can not only impact behavior and more efficient learning, but also participants’ overall well-being—especially if the taught program has direct consequences for one’s job, pay, career, and other aspects that can affect the quality of life.

Context plays its part on motivation, too. Many years ago, I taught a course at Nazareth College, near Rochester, New York, called Intrinsic Motivation in the Workplace. Since I considered it hypocritical to award grades in a course designed to teach people to see the inherent value in what they were doing, I arranged with the dean to not give traditional grades at the end of the course, but to indicate “pass” or “fail” on the students’ transcripts. I had a rebellion. The students were furious. They wanted their A. They were business students, adults already immersed in corporate settings and business culture. They complained that the class just couldn’t be worthwhile if they didn’t earn a grade. In what might be the ironic coup de grâce, they wondered how they would know if they’d worked hard enough if they didn’t get a grade. The system of motivation in place on campus was so overwhelmingly skewed toward rewards (i.e. grades) that the students tolerated no single exception to the system. On a grander scale, we have to ask how motivation is affected by the system in which it’s embedded.

FROM THE OUTSIDE IN: MOVING PARTICIPANTS TOWARD SEEING A VALUE PROPOSITION

Most motivational strategies are applied from the outside to the individual, as in the reward strategies discussed above. When the strategy is applied from the outside, it is perceived as (and, in fact, is) controlling. Whenever a participant is controlled, influenced, manipulated, or coerced, long-term and negative consequences arise. Money, grades, and other rewards can be manipulative. So too, are value systems, cultural concepts, and organizational structures (like employee-of-the-month, or class rankings). When a motivation strategy is controlling, its benefits are only of a short duration. Yes, their effect can be measured quickly, but reward strategies distract the participant’s attention from what’s really in it for them, replacing the intrinsic value of the learner with the “value” of the reward. The result is lowered intrinsic motivation. Our goal as trainers should be to come as close as possible to creating an intrinsically motivating environment. Along the way, learners are led to see the value of the training proposition, to them, and to the organization.

WHAT’S YOUR INTENTION?

If we begin by asking ourselves why we’re offering training, we’re hopefully bound to uncoverour intention. Each decision we make is informed by that intention, so we might as well come clean with ourselves right up front. Say, we’re scheduled to deliver training on a compliance topic, such as sexual harassment or an ethics policy (which is often just an excuse to cudgel people not to disclose company secrets). Is it fair to say our participants sometimes feel a little punished and resentful, just to be dragged into the training? So, why are we doing it? If our answer is, “It’s mandated,” what does this mean for our participants? From the get-go, our intention is not about them. It’s about us, the mandate, and our butts (a not-so-subtle CYA reference). The training is a waste of time then, from a learning standpoint, especially if participants consider themselves compliant already, of if they consider the training useless on the job, or if the material is dead, dull, boring, and painful. Simply put, the training isn’t relevant to them. Then we’re stuck trying to get them to learn in spite of themselves.

SELF-DETERMINATION THEORY

If we decide a session is about helping our participants to see the value in the training, to feel competent and autonomous to use compliant behavior, and to know we’re in this together, then the training is more about the participants and their learning. Our intention, then, will drive design and training decisions. We better ask ourselves, “What’s the goal of this training?” If we link the learning objectives to business results, we’re half-way home. If we link the business results to a value proposition specific to participants, even better.

Now we’re going to dive deeper into Self-Determination Theory and look at how when those basic three psychological needs of competence, autonomy, and relatedness get met, learners are more likely to experience a transfer of learning and yield better outcomes. Self-Determination Theory, when applied appropriately, can help trainers achieve greater results than reward strategies alone. By creating supportive components for how a learner can meet her needs in your classroom, you can increase the likelihood learning actually occurs and transfers back to the job.

WHERE DOES MOTIVATION COME FROM?

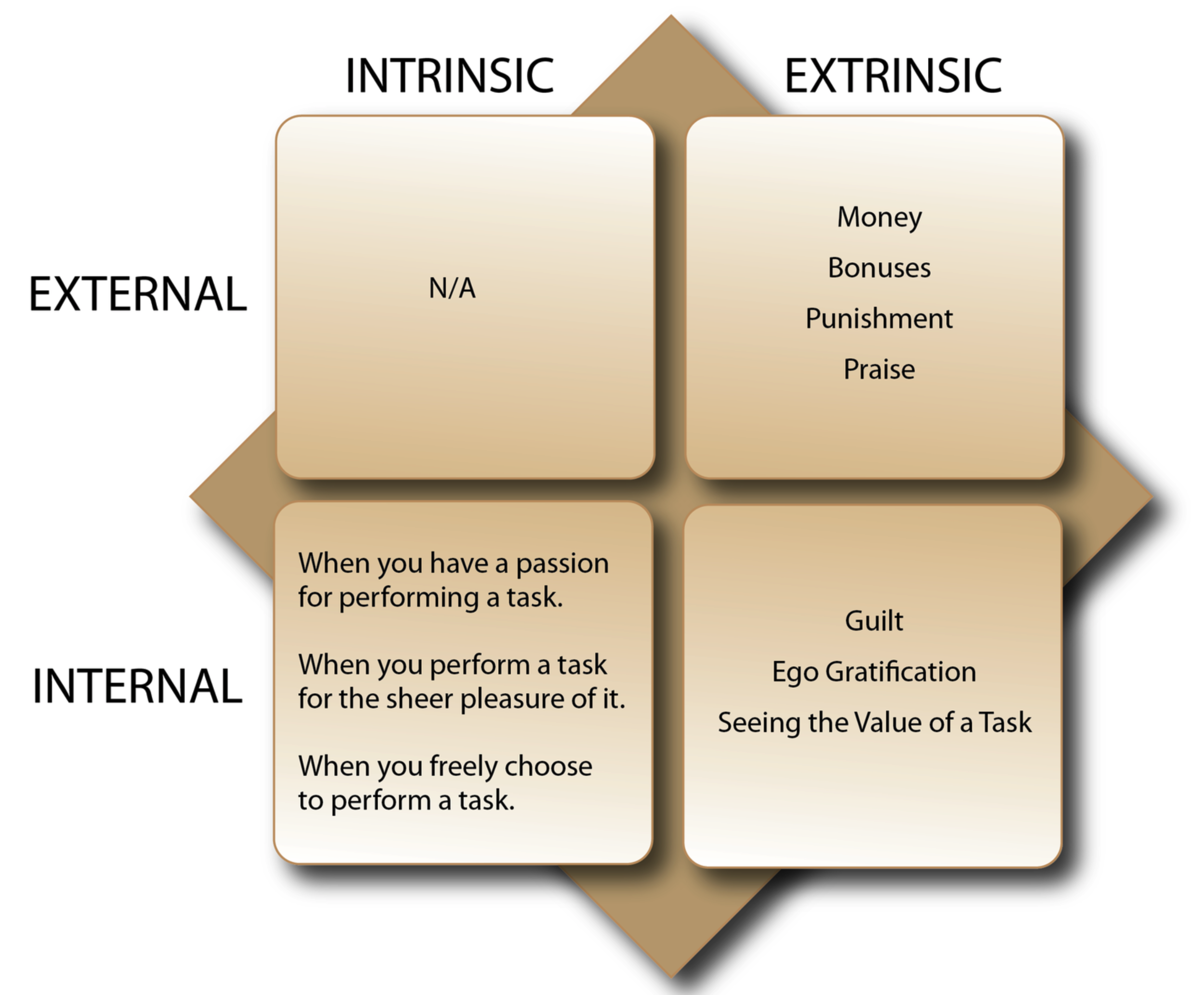

The idea of internal and external motivation is easy to grasp. If I raise my hand and answer questions correctly in a training session because I’m $1 richer for doing so, I have been externally motivated. If I answer the question because it makes me proud of myself or because I take great pleasure in responding, I have been internallymotivated. The better and more useful distinction is actually between which type of motivation is controlling and which is more autonomous. If I do a task mostly to receive $1, then that desire to get the money is controlling. If I do a task because my ego gets stroked or I feel better about myself—my pride is salved—I am still controlled, but this time by an internalized feeling affecting my ego. Other controlling feelings might be guilt, a sense of obligation or duty, or the seeking of approval from another. These feelings all distract from a more intrinsic approach toward the task at hand. Or, I have a strong sense of purpose, or even pleasure, when doing the task… a more autonomously oriented sensibility for the activity.

But start here… when you are motivated, you are motivated in one of two ways:

Intrinsically: Intrinsic motivation occurs when you are passionate about a task and perform it for the sheer pleasure of doing it. The motivator originates within you. Not all internal motivators are intrinsic.

Extrinsically: Extrinsic motivation occurs when you perform a task because some force, either external to you (money, rewards, grades, punishment) or internal to you (a value or belief that impacts your self-worth) drives you to perform. That driver is controlling in some way and to some smaller or larger degree.

This table shows which internal feelings are extrinsic because they are more controlling and originate (or are caused) by outside sources.

THE MECHANISMS OF MOTIVATION

We’ve been discussing extrinsic motivation quite a bit in this article, thus far. Whenever we discuss rewards and recognition strategies in a system (or training session), we’re referring to external motivation. As mentioned, extrinsic motivation, however, can also arise within the individual. On the next page is a variation of what Deci and Ryan call the Continuum of Self-Determination.

APATHY

Have you ever gotten in front of a classroom and seen long faces, disheartened souls, and completely miserable participants? Usually this occurs in highly technical programs for highly non-technical people, or highly flaky (interpersonal) topics for people who have a great aversion to members of humanity. Essentially apathy, or amotivation as Deci and Ryan refer to it, occurs when participants are forced to learn material they believe they have no competence to learn.

Let me give you a non-learning example. I can’t ski. If you put me up on the top of a mountain,slap some skis on me, and put a gun to my head, forcing me down the slope, I will do it, knowing full well that the likelihood of my dying is only slightly lower than dying from the bullet to the head. I feel utterly and completely incompetent—no skill, no ability, and certainly no knowledge to ski down a mountain, and yet I would be compelled to do so. That visceral feeling of hopelessness and helplessness in the face of doing something that feels completely impossible is amotivation. Learners don’t face their own mortality in the classroom (I hope), but being forced to learn something they feel incompetent to learn is no less frustrating or scary. My skiing example is to the extreme, but hopefully illustrative. When participants fall into this frustration zone, it’s our job as trainers to get them out of it as quickly as possible. This is an appropriate time to offer rewards as a way of introducing the possibility of competence. Remember, competence is all about the learner’s perception of it. You can create small milestones that are easier to attain and step a participant literally step-by-step, using rewards to inspire possibility.

REWARDS, PUNISHMENT, AND OTHER CONTROLLING FACTORS

Think of this part of the continuum as the “carrot and stick” section. I’ve said a lot about the effects of rewards and can’t emphasize enough the often detrimental effects they have on a learner’s intrinsic motivation. So let’s just summarize. Rewards:

Devalue the focus on learning for learning’s sake.

Demotivate those who don’t achieve them.

Crowd out other possible areas of interest.

Reinforce a Machiavellian approach to learning and reroute the goal to achieving the reward, and not the learning objective.

Require the continuation of subsequent rewards.

External motivation means just that. The reinforcement comes from outside of the person and controls, forces, cajoles, or strongly influences participant behavior. Externally motivating tactics are extremely powerful when the goal is short-term behavioral change. That’s the obvious reason why parents, teachers, bosses, government officials, and animals rely on external motivation as the most efficient catalyst for behavioral shifts. Long-term, however, the short comings are often perilous to authenticity and overall well-being.

INTROJECTION, THE GUILT FACTOR, THE EGO THING, THE “SHOULD” FACTOR, AND KFKD: Extrinsic Motivation from Within

According to Deci and Ryan, sometimes we are motivated by an internal factor that is not intrinsic, which they call introjection. Call it guilt. Call it ego. Call it, as Anne Lamott does, a radio station inside her head, tuned to the most judgmental critic and nag imaginable. (She calls it, “KFKD,” and I’ll let you sound it out.) We don’t want to do something, but because we believe we should, we do.

Our self-esteem and self-worth are threatened or stroked, depending on what we think of our behavior. You recognize this motivator in your training session when a participant has forced herself to volunteer for something when she’s clearly uncomfortable. She may be telling herself that she’s bound to fail, but because her boss has sent her to this training, she feels she should volunteer. She’s been motivated by a factor extrinsic to her own self (the boss’ expectations) expressed from within. As a motivator, introjection can be powerful, but it doesn’t often result in sustained excellence. For example, when my daughter Lia was three, she came up to me with tears in her eyes. She said, “Daddy. You’re going to die. I don’t want to be a ‘porphan.’” I looked at her, quite confused, and asked what she meant by all this. She told me very seriously that I was fat, and that I ate too much, and needed to ‘pexercise.’ Then she sobbed and asked me not to leave her alone. At three, Lia was impossible to resist (and still is at the ripe age of 17). That afternoon, we went to an exercise equipment store and purchased a treadmill. The first week, she would sit right next to me as I walked, urging me to go faster and ensuring that I completed my 45 minutes. By the second week, she would only get me started before she explained that she had other things to do. By the third week, the treadmill was in the basement. This is a good example of the long-term effects (or lack thereof) of introjection on behavior. While ego gratification, seeking approval, or guilt may have a longer effect than rewards, the long-term effect is still negligible.

SEEING THE VALUE: Getting Closer to Intrinsic, but nonetheless still Extrinsic Motivation

Another extrinsic motivator is the ability to see value. Though you are not doing the task because you freely choose to and you passionately want to, you have internalized its overall importance. This type of motivation is actually quite close to intrinsic motivation. However, seeing value is still extrinsic, because the sense of importance originates from an outsidesource. For example, a man might quit smoking, because he knows it is good for his health. He knows he will have more energy. And he knows he will save money on dry cleaning. You’ve noticed the participants in your training sessions who see value in what you’re doing. They’re not dying to be there, but they appreciate that it’s good for them. They have identified the value and internalized it. Over time, that value may become more and more intrinsic to them, or, as Deci and Ryan say, integrated. Helping your participants see what’s in it for them is a good strategy for trainers to employ. Remember, the more participants value the purpose and meaning behind what they do, the more autonomous they will feel. Facilitating training relevance moves participants along the continuum toward intrinsic motivation, where passion motivates behavior.

INTRINSIC MOTIVATION

Intrinsic motivation is synonymous with passion. As a trainer and an instructional designer, I have seen passionate learners in corporate settings. Although frankly, this is rare. Intrinsic motivation means that your participants have freely chosen to engage in the learning opportunity and completely believe they can do what it is they’re learning. I use simulations and games frequently as a way to engage learners to a degree where they no longer think about or reflect upon their competence. Essentially, when they’re having fun or are engaged, they don’t perceive their own objective incompetence. The more relevant and applicable the activity (game or simulation), the more likely the participants see value or, if I’m lucky, freely choose to do it.

SO… WHAT TO LOOK FOR

I hope by now you agree that creating a more intrinsically motivating environment is essential in all learning situations. However, it is important to identify when motivation, or a lack thereof, is the root cause of a learning challenge. Most people struggle to properly identify their own motivation. It is nearly impossible for a trainer to properly diagnose another person’s motivation, too. But, we can affect the environment and how learners’ may find ways to get their needs satisfied.

Some key indicators that a motivation intervention is needed are noted below. These are all signs that a person is challenged or frustrated or even bored. They are possible indicators a learner is coerced or forced into the learning situation rather than choosing to engage. Or, the learner feels disconnected from the rest of the cohort. Any way you look at it, there are often signs you need to adapt the environment in some way. We can always be better at proving more structured support for learner competence, providing more autonomy support, and involving learning more to support their need for relatedness. So, here are just a few of those potential indicators:

When a participant does not believe she is capable of learning a new task – either stemming from an inability (she doesn’t have the prerequisite knowledge or skills) to learn the new competencies or the incapacity (the necessary resources or time) to complete the learning activities. She might complain, “I don’t know how to do that…” or “The trainer did not give me the resources to do that…” or “I feel overwhelmed…”

When the participant does not believe that he has a choice in learning the task. He might complain, “I don’t have a say in how this should be done…” or “I have no choice. I have to do this…” or “Why is this important?” or “Why are we even doing this activity?”

When a participant does not feel like she belongs to the learning cohort. She might complain, “I don’t belong here…” or “No one likes me…” or “I just don’t fit in…”

When a participant sees no end in sight and believes that nothing he does matters. He might complain, “What’s the point of this stupid activity? This is a waste of time and will never get me to the goal...” or “No one ever listens to us, why do I even bother? We don’t need this.”

When a participant does not receive any kind of feedback about her performance. She might complain, “I haven’t received any indication I am getting better at this…” or “I don’t know what the trainer thinks…”

When a participant is more concerned about rewards and consequences. He might complain, “What do we get for doing that?” or “I’ll only play if they pay…” or “If you want me to do that, what do I get for it? Can I level up in the game?” Or, “Do we get promoted once we complete this course?”

When a participant is more concerned about peer approval, trainer approval, or management approval. She might say, “I’ll do it as long as no one gets mad at me or looks at me funny.” Or, she asks for constant check-ins with the trainer.

When a participant appears to lack excitement about the workshops and disconnects either mentally or physically frequently. He might say, “I’ve learned how to ace this and I can work more quickly than others.” Or, “I don’t need to be here.” Or, “I have too much work to do back on the job.” Or, “I have to go… I have another call to take.”

WHAT YOU CAN DO

In the end, as mentioned, you cannot directly motivate your learners. But you can influence them by tactically affecting the learning environment. Here are some ways to directly have an effect on each of the three basic psychological needs which in turn influence how likely your participants will either see the value of your program or even have an increase in their intrinsic motivation to learn.

SUPPORT COMPETENCE:

Provide structure. Be sure you have clear expectations, classroom protocols, and goals.

Make sure participants are aware of the program logistics (start and end times, breaks, lunch, etc.).

Ensure there are appropriate job aids and references that support learning in the classroom and afterwards.

One cannot get better at a new task without proper feedback and evaluation. Be sure participants receive both and then have opportunities to try again.

Leverage good learning science, like applying spaced repetition and other facets to good instruction design.

Adapt your delivery to maximize the challenge. If you notice frustration, simplify. If you notice boredom, increase the difficulty.

AUTONOMY SUPPORT

Provide learners with choices in how to engage with the learning experience.

Be sure to explain and then facilitate discussions around the purpose and meaning of the program and the individual activities.

Always explain the reason you are doing what you do.

Demonstrate and share the relevance of the activities in the program.

Focus on engaging participants using games, activities, discussions, and more to foster enjoyment and immersion in the process. You don’t have to entertain. But you do have to engage interest.

Avoid using rewards and consequences that are not directly a result of the actual activities.

RELATEDNESS SUPPORT

Use activities to get participants to become more involved with each other and the overall program.

Inform and explain the process of the activities so participants know how to engage with each other.

Share information about the logistics and next steps with them.

Use pairs and small group work to foster relationships.

And while networking opportunities are not directly related to the learning goals, they do help bridge new relationships that will keep participants engaged with each other post-session.

CONCLUSION

Motivation is trickier than it looks. If a trainer wants to increase participation and decides that in order to do so, she will hand out dollar bills, she must know that she is possibly doing so at the expense of increased learning retention and relevance, substituting extrinsic motivation for intrinsic. As mentioned, money, reward structures, and gold stars do influence behavior, but they focus behavior on getting the external reward, not on really improving the task at hand. In a technologically rapid world, sometimes it is necessary to push behavioral modification through quickly. However, acknowledge to the learner what you’re doing, and strive to create, in parallel, a more intrinsically supportive training environment when possible.

Making the training relevant is of paramount importance. When a trainer focuses on improving the opportunities for people to meet their psychological needs (competence, autonomy, and relatedness), it is more likely that the trainer will get higher levels of satisfaction and morale, and foster a mastery-orientation among the participants, demonstrated by increased resourcefulness, concentration, creativity, and intuition. Creating a motivating environment takes more than just throwing money at the problem.

[1] While at the University of Rochester in the late 90s, I had the opportunity to spend several semesters of study with Deci and Ryan. It was a marvelous and life-changing experience. This article is my interpretation of their work applied to L&D. Any value offered here is derived from their research and any incorrect application is due to my own misinterpretation. Their work has inspired how I parent, engage in relationships, my career, and well… how I live my life. My appreciation for them knows no bounds.

REFERENCES

Deci, E. L., & Flaste, R. (1996). Why we do what we do: Understanding self-motivation. New York: Penguin.

Deci, E. L., Koestner, R., & Ryan, R. M. (1999a). A meta-analytic review of experiments examining the effects of extrinsic rewards on intrinsic motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 125.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2002). The “What” and “Why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11:4, 227-268.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2002). Overview of self-determination theory: An organismic dialectical perspective. In E.L. Deci & R.M. Ryan (Eds.), Handbook of Self- Determination Research (pp. 4-33). Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (Eds.), (2002). Handbook of self-determination research. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press.

Lamott, Anne. (1994). Bird by bird: Some instructions on writing and life. New York: Pantheon Books.

Ryan, R. M. (Ed.). (2012). The Oxford handbook of human motivation. New York: Oxford University Press.

Ryan, R.M., & Deci, E.L. (2017). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. New York: The Guilford Press.